The economic situation, which is not prominently reflected in the story of the Argonauts, appears to have been far less idyllic than legend suggests. Evidence indicates that the economic network encompassing the eastern shore of the Black Sea, the Aegean Archipelago, and surrounding regions formed a natural arc of interconnections. Once established, this network endured for a long time, with the exchange of goods serving as its backbone across different segments. Warfare and peaceful trade alternated throughout early antiquity, a pattern that persisted into later antiquity. The relationships between the early Georgian population and Greek tribes continued to evolve over the centuries, reflecting a blend of conflict and cooperation.

It is especially important to examine the situation in early Western Georgia during antiquity up to the 1st–4th centuries. Specifically, we need to assess the strength of the Georgian economy at that time and the structure of social life connected to it. If Colchis (Kolkheti) had its own social structure, this would imply a corresponding economic foundation. However, documentary evidence remains sparse. Although detailed information about Colchis’s economic and social conditions during this period is limited, the volume and nature of goods traded, along with the character of exchange counterparties, suggest that the Georgian tribes’ social structure was not based on a system of slavery. The significant production of goods in Colchis, collected for export, likely resulted from slave labor, supporting a surplus that enabled speculation. Roman officials stationed in Colchis were known to engage in such speculative activities occasionally.

The circulation of goods in early Georgian economy relied on slave production and primarily served its needs. Commodity production, as we understand it today, predates capitalist systems and also supported slave-based economies. This suggests that goods were produced under conditions of mass production, which would be difficult to reconcile with primitive, subsistence-level tribal farming.

Rome’s (and later Byzantium’s) political ambitions to conquer the eastern shores of the Black Sea were not mere expeditions of curiosity. The Black Sea harbors located in the Colchis region initially served as commercial trade hubs, only later taking on strategic importance. Ports such as Phasis, Dioscurias, and Petra were primarily centers of lively trade, driven by the buying and selling of goods. Although the historian Procopius of Caesarea describes a slightly later period—the 6th century—in his famous work The Wars of Justinian, the economic stagnation he reports in Colchis was not unique to just one or two centuries.

According to this account, the harbors along the Colchian coast of the Black Sea were bustling centers of trade between Byzantine and Georgian merchants. Goods likely arrived here from other regions as well, a fact noted by Procopius of Caesarea. Thus, other nations participated in the trade with the Colchians as active partners. We can infer that foreign merchants, including Byzantines, had their warehouses and living quarters here—forming a sort of “Greek district.”

The trading outposts and routes established in these centers were important not only for economic exchange but also for the spread of culture. In a way, these outposts became extensions of each nationality’s territory, exporting not only goods but also cultural achievements.

The key question for us is: was the presence of Greek traders significant enough to constitute a large-scale settlement, thereby creating conditions in certain parts of Colchis for Greek influence, not only economically but also culturally?

Only an approximate answer can be given to this question. Based on some preserved accounts, we can form a rough idea of Greek settlements in the area of ancient Phasis (modern Poti). According to these reports, some Greek merchants, like soldiers, remained in Georgia permanently. However, it seems that these settlements were not established under peaceful conditions, as the local population required constant protection.

Moreover, it appears that Greek settlers did not penetrate deeply into Colchian territory. Existing accounts indicate that a Byzantine (or Roman) military garrison was stationed at Phasis, within the fortress itself. Around the fortress, near the harbor, there were former military personnel—those who had been discharged from service—and merchants who stayed for extended periods. The stationed army was relatively small, suggesting that the local resident population associated with these settlements was also limited in number.

The most intriguing aspect is that the Greek population not only lived separately from the locals but that their living area was surrounded by a moat—likely constructed for more than mere separation. In any case, the Greek population does not appear to have been large, nor did they integrate with the native inhabitants. It is clear they did not consider themselves natives but remained distinct, with no evidence suggesting that Greek colonization of the eastern Black Sea coast, including Colchis, resembled the extensive colonization of the Ionian coast of Anatolia. While the Ionian coast became a cradle of Greek philosophy—developing schools like the Pythagorean school—such intellectual flourishing did not occur in Colchis.

It seems that, given the economic situation, there was no point in Kolkheti where the Greek (Byzantine) element could play a decisive or leading role in the socio-economic life of the region. The imperial power only formally exercised its governmental institution (royal power) and had its representatives. Later, though not much later in time, both the Eastern and Western powers needed to turn to the bearer of Kolkhian sovereignty, Gubaz, for emergency military strategies.

From a socio-political point of view, the slave-owning society was very early on the road to feudalization. If the information of some sources is correct, that the whole kingdom of Kolkheti already in the II century. From the first half, it began to be divided into separate principalities (kingdoms), then it becomes clear that this is not the result of external intervention, but must be the manifestation of internal socio-political processes.

The military aristocracy, which represented the ruling circle, gradually lost its influence. Themistius connects the development of cultural work and the creation of its focus with the weakening of the influence of this military aristocracy. He compares Kolkheti with its neighbors at that time and directly points out that the Kolkhites learned military skills in the new conditions – riding, archery, flying the eagle, and “participating with the Muses”.

The Romans (and later Byzantines), driven by economic interests, sought to control Colchis without dismantling its local governance, instead adopting a policy of external oversight. By the 4th century, Roman-Byzantine legal relations with the kings of Colchis appear to have been primarily superficial and formal, reflecting a strategy of indirect rule rather than direct integration.

From a socio-political perspective, the slave-owning society was very early on the path to feudalization. If the information from some sources is correct, and the entire kingdom of Kolkheti began to divide into separate principalities (kingdoms) as early as the second century, then it becomes clear that this was not the result of external intervention, but rather a manifestation of internal socio-political processes.

The military aristocracy, which represented the ruling elite, gradually lost its influence. Themistius links the development of cultural activities and the establishment of a cultural center with the weakening of this military aristocracy’s power. He compares Kolkheti with its neighbors at the time and directly points out that the Kolkhites acquired new military skills—such as horsemanship, archery, falconry—and “participated with the Muses.”

Of course, the Greek source in this case cannot conceive of the intellectual achievements of Colchis and its cultural communion in general, except as the assimilation of Greek philosophical and cultural accomplishments. In reality, the progress and interests of Kolkheti primarily reflect its economic and social conditions. The philosopher Bakur, who is discussed below, already held certain philosophical views when he moved to Kolkheti, and therefore, he did not adopt these views while in Kolkheti.

The rhetorical school of Kolkheti had a more practical focus: it trained court figures—defenders and accusers—and was thus closer to Aristotle’s rhetoric. This explains the appeal of this school to the Greeks, and in particular to Themistius, who was not so much a Neoplatonist as a supporter of Aristotle. The practical activities of giving and receiving led to the need for a proper school. The counterparts in trade relations were mostly, on the one hand, Colchis and, on the other, the Greeks. Therefore, future judicial and public officials needed to be well-versed in the language of both sides. This also meant that instruction in the school of rhetoric had to be conducted in two languages. The public competition, mentioned in the Greek sources, also required proficiency in both languages.

Thus, it becomes clear that the rhetorical high school of Kolkheti was established by the demands of commercial interests. The art of oratory, exemplified by the orators of Colchis and Lazes, is the best indicator of the results and nature of the education provided by the rhetorical school of Kolkheti.

Thus, it becomes clear that the rhetorical high school of Kolkheti was established by the demands of commercial interests. The art of oratory, exemplified by the orators of Colchis and Lazes, is the best indicator of the results and nature of the education provided by the rhetorical school of Kolkheti.

There is no evidence that the rhetorical school of Kolkheti served religious or, even more so, Christian-theological interests. Nothing of this sort has been preserved in the material related to the school or the orators of Bakur and Kolkheti. The question of religion—whether ancient pagan or Christian—is entirely absent from the activities of the rhetorical school of Kolkheti. It appears that neither the ruling aristocracy nor the religious officials had a vested interest in this matter.

Which group or class ideology is expressed by the work developed around the rhetorical school of Kolkheti? The answer to this question is difficult, but one thing is clear: the philosophical currents of the pre-Marxist period were not characterized by mass appeal. They were not, and could not have been, expressions of the thinking of the masses. At best, they could represent the philosophy of a particular school.

But it is one thing to have a school, and another to have a specific kind of school. From the perspective of the public class, the higher rhetorical school of Kolkheti expressed the practical purposefulness of the trade circles. It was not connected to ecclesiastical or theological speculation, nor to the idealism and metaphysics of ancient philosophy, although it was secular.

These are the results of the economic and socio-political conditions that led to the creation and functioning of the Higher Rhetorical School of Kolkheti.

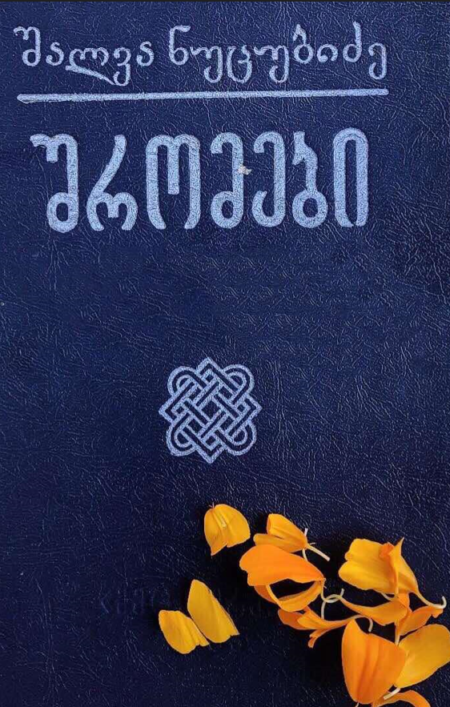

Author:

Shalva Nutsubidze

1983

Translated from Georgian by Elene Shengelia.