Among the monuments of Georgian wall painting from the first half of the 12th century, the Gelati mosaic holds a special place. It is preserved in the nave of the main cathedral and dates precisely to 1125–1130.

Mosaic painting, in line with the tradition of Georgian art, adorns the altar corner. The rest of the church was originally decorated with frescoes, most of which have been renovated at various times. In the western narthex of the church, frescoes from the time of its construction remain, depicting the ecumenical councils.

The coexistence of fresco and mosaic art in a single monument is unique in Byzantine art. At the center of the composition, against a golden background, the Virgin Mary is depicted in full figure, with her head slightly inclined. On either side of her, the archangels Michael and Gabriel appear in a reverent pose. The depiction of the Virgin Mary in the Gelati mosaic, a subject common in Byzantine monuments (e.g., the mosaic at the southern gate of the Karina Chapel in Nicaea, Venice, and the Church of St.), features a slight tilt of the figure, adding a sense of dynamism not seen in Biturzan art.

A comparative analysis of the images of the Infant Virgin Mary and the angels standing before her in Georgian, Byzantine, and Eastern Christian art reveals that they are based on the ‘Nikopei’ type of the Virgin Mary, who, from the time of Emperor Maurice, was considered the patroness of the imperial house. Several variants of the ‘Nikopei’ type of the Virgin Mary’s image can be identified, distinguished by the placement of the figure of Emmanuel and the presence of angels or representatives of the imperial house standing before her. A close parallel to the Gelati mosaic can be found in examples such as Aten, Ifrari, and others.

In the Gelati mosaic, the Byzantine tradition is subtly altered. The figure of the Virgin Mary is slightly tilted to the right, creating a sense of relief in her depiction, with her blue robe contrasting against the golden background of the painting. This deviation breaks from the solemn, monumental style of conch compositions typically observed in the wall paintings of Sicily and Byzantium. The dynamism of the Infant Virgin Mary’s image is further emphasized by the calm and composed poses of the archangels Michael and Gabriel standing beside her.

The introduction of dynamism into the central composition of the conch painting was a completely new and bold artistic technique, first pioneered in the monumental art of this era by the ingenious master of the Gelati mosaic. This technique represents a new artistic phenomenon characteristic of the monumental painting from the era of David the Builder and Demeter I, which later found further development in the monumental art of Queen Tamar’s time.

A small, elongated chin, a slightly noticeable second mouth, and a chin pointed subtly downward are characteristic features of Byzantine art and the depiction of the Virgin Mary, as seen in the mosaics of the Panagia and Nikia temples in Cyprus and the art of Mokur in St. Sophia. Although these monuments belong to different periods and styles, they share an underlying foundation that creates an Oriental-Greek artistic color. A distinctive feature of the Virgin Mary in the Gelati mosaic is the elongation of her facial features, including a prominent chin, a clearly elongated forehead, a narrow upper eyelid, and a small, curved lip. Compared to the Virgin Sophia mosaic, the Gelati depiction is modeled with greater relief, and the arrangement of mosaic stones is denser.

The Gelati mosaic does not depict a baby but rather the child Emmanuel. The posture of his tall, freely seated figure and his generally stern expression align fully with the theological and dogmatic understanding of the Emmanuel type.

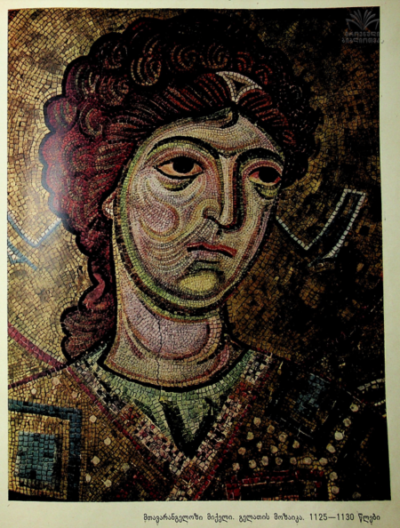

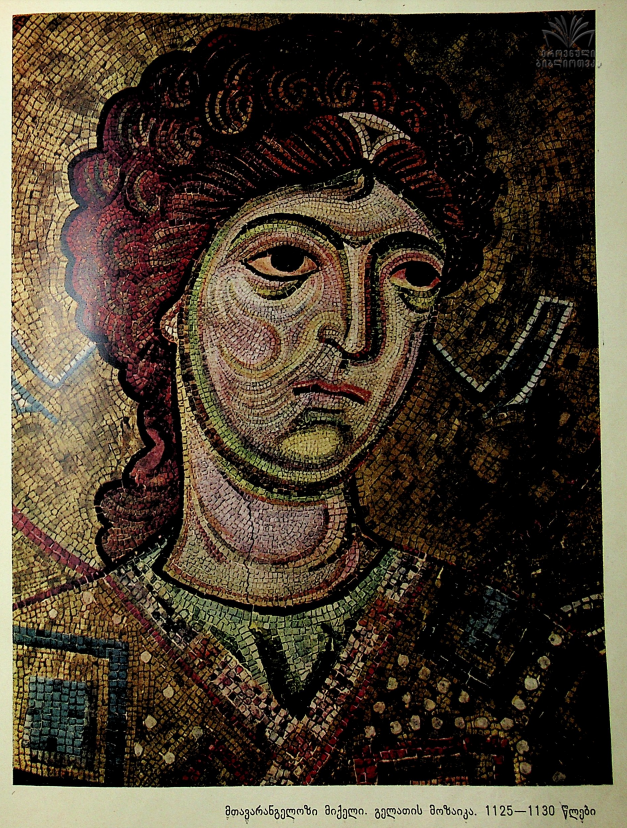

The master of the Gelati mosaic imbued the traditional iconographic images of the Archangels Michael and Gabriel with a unique expressive quality and depth. The stern face of Archangel Michael, representing the heavenly army, is contrasted with the lively and intricately modeled face of Archangel Gabriel, the herald of God’s will. This striking juxtaposition of the angels’ elaborate clothing and the distinct coloring of their faces, along with the masterful integration of the Archangels’ overall palette with the central composition, represents a fundamentally new phenomenon in the mosaic art of that era.

From an artistic perspective, the Gelati mosaic is a deeply conceived and flawless work of monumental painting, which, in terms of its overall cultural significance, stands alongside the most advanced wall paintings of the first half of the 12th century. The artist carefully studied each detail of the composition and harmonized them both compositionally and in terms of technique, drawing the viewer’s attention to the Virgin Mary and Emmanuel. The master of the Gelati mosaic emerges as a great innovator in monumental painting. He broke with the artistic traditions of Byzantine art, infusing the central composition of the altar’s apse painting with dynamism and life.

Author: Shalva Amiranashvili

1971

Translated from Georgian by Elene Shengelia